This month is my “baby” sister (14 years younger) Michelle’s time at the lake (she owns 1/3 of the cottage, I own 2/3). She said that since she wasn’t able to visit when I was having chemo and radiation, she wanted to give me a lake-spa weekend. She’s new to yoga this year, passionate about it, learning moves and practicing the techniques of “healing yoga” for herself. I had a session every day on the upstairs screened-in porch, waves lapping below, incense burning, woo-woo music on Pandora, and a little sister who loves me. If anything can cure a body, that ought to. Touch makes a huge difference, I think, not just when we’re sick. A masseuse is good, but someone who loves you is even better.

This month is my “baby” sister (14 years younger) Michelle’s time at the lake (she owns 1/3 of the cottage, I own 2/3). She said that since she wasn’t able to visit when I was having chemo and radiation, she wanted to give me a lake-spa weekend. She’s new to yoga this year, passionate about it, learning moves and practicing the techniques of “healing yoga” for herself. I had a session every day on the upstairs screened-in porch, waves lapping below, incense burning, woo-woo music on Pandora, and a little sister who loves me. If anything can cure a body, that ought to. Touch makes a huge difference, I think, not just when we’re sick. A masseuse is good, but someone who loves you is even better.

AND, I finally got in the lake! I swam my usual swim to the boathouse three cottages down and back. We’ve always claimed the waters of our lake are the North American Lourdes, so I guess I’m doubly “cured.” But I have to say, my poor muscles are weak. It was a simple swim, breast stroke, not far, but it registered all over my body. Still does.

I put on my swim cap ordered from one of the cancer sites. It’s white and ruffled and comes down over even my ears. It’s dopy. I look like Esther Williams. Michelle said something like, “Oh for Pete’s sake, take it off.” So I did. Here’s a photo, from a safe distance, but I put the cap back on when there were boaters or neighbors. And the photo Michelle took of the two of us, up close, my head shining in the sun? I can’t quite show you that one. I’m shy, obviously, about my head.

I know, I know, a lot of young (particularly) people parade their bald heads around, an act of defiance of the disease, a statement that they feel okay no matter what they look like. I’m okay being bald, but I don’t like to be stared at, or have eyes drop when they see my head. I’m private. I’m okay with that.

I have days when I can walk over a mile, other days, like today, when I feel that chemo-y sick feeling and every movement is an effort. There seems to be no clear cause of either. My body just oscillates between okay and not-okay.

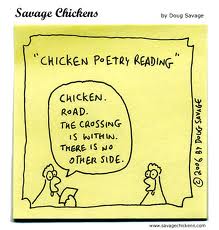

I feel somehow deficient that I haven’t been turning out poems about the cancer. Other people have written really good poems about it. Though I’m reminded of what I said in my essay, “Mildred,” in Sydney Lea’s and my book (Growing Old in Poetry, on Kindle from Autumn House. Ahem. Also a short version on Brevity’s website): you have to see things slant, you have to wait until they insinuate themselves in when the eyes are turned elsewhere. I’d tried to write a poem about my adventure with Mildred the raccoon, but it was a failure. I’ve tried to write poems “about” this cancer experience. I only like one or two of them, if that.

“Emotion recollected in tranquility,” says Wordsworth. I say, if it’s tranquil, it’s lost its punch and you might as well not write it at all. However, if you let it sit, it will attach itself to the shirttail of some new urgency and both will be charged by it. Why did WW say “recollected”? Anything written about is recollected. “Tranquility” because almost certainly there’s much more to the poem/essay/story than the present scene yet knows. There’s a breadth and depth to be brought to bear upon it. There’s an assimilation that, if it happens, opens the door of the experience to let in the whole of our lives.

This relates to privacy, too, I think. If we scatter ourselves all over Facebook, if we don’t allow enough pulling-back time, if we release every experience immediately into the general churning vat of conversation, OR (Ahem again) onto our blogs, how can we absorb, assimilate, and “see” what’s there? I’m not talking about making meaning of it, which is more akin to preaching than to writing. I’m talking about seeing by staying with it, by continuing to watch what emerges instead of quickly ossifying it into language, photos, and emoticons.

This relates to privacy, too, I think. If we scatter ourselves all over Facebook, if we don’t allow enough pulling-back time, if we release every experience immediately into the general churning vat of conversation, OR (Ahem again) onto our blogs, how can we absorb, assimilate, and “see” what’s there? I’m not talking about making meaning of it, which is more akin to preaching than to writing. I’m talking about seeing by staying with it, by continuing to watch what emerges instead of quickly ossifying it into language, photos, and emoticons. ![]()