- Well, I just haven’t. I haven’t posted in a long while. There’s been a great deal of caretaking around here, although Jerry does everything he can. Yesterday I saw him dragging the dirty clothes basket along behind his walker, making for the laundry room.

- Have I lost focus? Once I wrote about cancer, but that subject, thank whatever-gods-may-be, is worn out for the time being. I have thought if I use what precious writing energy I have on a post, I won’t have anything left for the poems and essays.

Yes, but of course energy begets energy. And when has not having anything to say stopped the words? They come out ahead of consciousness, sometimes. They know what they want even when “I” don’t.  Aging. Aging and the writer. That subject should keep me busy for a long while. Today the subject is caretaking. There are probably two dozen good blogs about caretaking out there. And books. You don’t need to bother with this blog. However, I hope you do. Breathes there a caretaker with soul so dead that he or she doesn’t sometimes flare with internal anger, doesn’t watch others head out on mountain biking trips and feel jealous? Who doesn’t fantasize living alone, eating toast over the sink instead of bothering to get out breakfast stuff? Who doesn’t stare long minutes out the window at the turning trees?

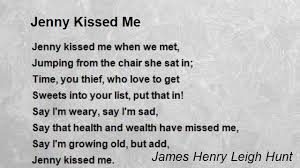

Aging. Aging and the writer. That subject should keep me busy for a long while. Today the subject is caretaking. There are probably two dozen good blogs about caretaking out there. And books. You don’t need to bother with this blog. However, I hope you do. Breathes there a caretaker with soul so dead that he or she doesn’t sometimes flare with internal anger, doesn’t watch others head out on mountain biking trips and feel jealous? Who doesn’t fantasize living alone, eating toast over the sink instead of bothering to get out breakfast stuff? Who doesn’t stare long minutes out the window at the turning trees?  There’s no point in trying to balance that with heart-warming tales of the blessings of sharing hard times, of having a long-time mate that you love, no matter what. The deepening of tenderness and closeness when it’s down to brass tacks. No sense balancing at all. It’s not one or the other, but both.(Above poem is my 100-year-old father's favorite. Thought you might enjoy it.) Things have turned mysterious. First there was Jerry’s hip replacement, then it failed, then it was replaced again. For a short time there was no pain. In the last couple of weeks there is a lot of pain in the area of the sacrum. He’s had steroid injections. No help from that yet. We don’t know exactly what’s pressing on what, but after two major back surgeries, plus the hip surgeries, is there any wonder something’s pressing on something that it shouldn’t be. Can this be remedied? I don’t even know what we’ll have for lunch, much less what will transpire tomorrow.

There’s no point in trying to balance that with heart-warming tales of the blessings of sharing hard times, of having a long-time mate that you love, no matter what. The deepening of tenderness and closeness when it’s down to brass tacks. No sense balancing at all. It’s not one or the other, but both.(Above poem is my 100-year-old father's favorite. Thought you might enjoy it.) Things have turned mysterious. First there was Jerry’s hip replacement, then it failed, then it was replaced again. For a short time there was no pain. In the last couple of weeks there is a lot of pain in the area of the sacrum. He’s had steroid injections. No help from that yet. We don’t know exactly what’s pressing on what, but after two major back surgeries, plus the hip surgeries, is there any wonder something’s pressing on something that it shouldn’t be. Can this be remedied? I don’t even know what we’ll have for lunch, much less what will transpire tomorrow.  Meanwhile, Jerry’s just celebrated his 78th birthday. We’ve had to give up our Alaska cruise, which was to be our present to each other. Note to reader: buy trip insurance (we did). We drove up the peninsula to look at trees and gorgeous water, the way old people do, and stopped for lunch along the way. My sister and brother in law picked up dinner for the four of us and brought it to our place. My children and grandchildren travel all over the place. Kelly’s family was in Croatia this spring. Scott’s in Italy right now. Interestingly, I have always been pretty content with a computer, paper, pen, trees, crickets, and water to swim in. I prefer our lake but I can make do with the Y. There are all sorts of explorations, both interior and exterior. I lean toward the interior, anyhow. The interior has its own cathedrals and canals. In less than two weeks, I’ll have arthroscopic surgery to repair a torn meniscus that has tormented me for almost six months (took a while to diagnose). I’ll be glad to get it fixed, but there’s Jerry, unable to help while I’m hobbling or whatever I’ll be. I mention this because this is how it is when you get old—people’s ailments don’t conveniently take turns. They sometimes come on simultaneously. Meanwhile, I’ve written a couple of essays I’m happy with this year, and more poems, good and bad, than I usually admit to. I tend to pretend I’m a total wuss as a writer. It seems to be my way of clearing the decks for the next thing.

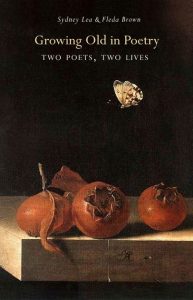

Meanwhile, Jerry’s just celebrated his 78th birthday. We’ve had to give up our Alaska cruise, which was to be our present to each other. Note to reader: buy trip insurance (we did). We drove up the peninsula to look at trees and gorgeous water, the way old people do, and stopped for lunch along the way. My sister and brother in law picked up dinner for the four of us and brought it to our place. My children and grandchildren travel all over the place. Kelly’s family was in Croatia this spring. Scott’s in Italy right now. Interestingly, I have always been pretty content with a computer, paper, pen, trees, crickets, and water to swim in. I prefer our lake but I can make do with the Y. There are all sorts of explorations, both interior and exterior. I lean toward the interior, anyhow. The interior has its own cathedrals and canals. In less than two weeks, I’ll have arthroscopic surgery to repair a torn meniscus that has tormented me for almost six months (took a while to diagnose). I’ll be glad to get it fixed, but there’s Jerry, unable to help while I’m hobbling or whatever I’ll be. I mention this because this is how it is when you get old—people’s ailments don’t conveniently take turns. They sometimes come on simultaneously. Meanwhile, I’ve written a couple of essays I’m happy with this year, and more poems, good and bad, than I usually admit to. I tend to pretend I’m a total wuss as a writer. It seems to be my way of clearing the decks for the next thing.  AND, the book I wrote with Sydney Lea, Growing Old in Poetry: Two Poets, Two Lives, has just come out in paperback from Green Writers Press in Vermont. It has a great cover and a new chapter on politics. It’s gotten great response from people who’ve gotten hold of it. I ought to have a book launch! This needs to be another blog post—the need to publicize when you get older and basically all you want to do is write.

AND, the book I wrote with Sydney Lea, Growing Old in Poetry: Two Poets, Two Lives, has just come out in paperback from Green Writers Press in Vermont. It has a great cover and a new chapter on politics. It’s gotten great response from people who’ve gotten hold of it. I ought to have a book launch! This needs to be another blog post—the need to publicize when you get older and basically all you want to do is write.