The hair thing. I can pinch my “bangs” between thumb and forefinger. At the back, hair’s about twice as long. I try a hairbrush and see a slight difference. Not much, but it’s coming along. It feels like healing. That’s the wonderful thing about hair. The more of it, the better I am. From the front, it’s cute, but from the sides and back—of course I stand with a mirror and study it—it’s still plastered to my head in a way that isn’t flattering.

The hair thing. I can pinch my “bangs” between thumb and forefinger. At the back, hair’s about twice as long. I try a hairbrush and see a slight difference. Not much, but it’s coming along. It feels like healing. That’s the wonderful thing about hair. The more of it, the better I am. From the front, it’s cute, but from the sides and back—of course I stand with a mirror and study it—it’s still plastered to my head in a way that isn’t flattering.

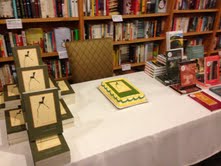

[None of MY hair in these photos. They're all from the book launch. I wanted you to see them.]

Upside: my hair may grow slowly, but it’s thick, as thick as it always was, it seems. It’s steely gray, coming to a point of gray at the front, whiter on the sides. Patchwork. The lower back is darker gray, the crown and upper back is lighter gray. As it gets longer, the unevenness doesn’t seem so radical.

Now that I can see the crown, the cowlick, and the growth pattern, I can see I’ve been parting it the best way all along. Some beauticians have said the part should naturally fall on the right, but they were wrong.

Now that I can see the crown, the cowlick, and the growth pattern, I can see I’ve been parting it the best way all along. Some beauticians have said the part should naturally fall on the right, but they were wrong.

I do not tire of this analysis. A once-in-a-lifetime (one fervently hopes) chance to see what’s under there, like tracing my own development, hairless baby to eventual full head.

I’m tired of the wig, but when I look at me without it, I’m not yet happy with what I see. Too severe, too wild.

It seems as if I’m slowly watching myself come back together. I am having cataract surgery tomorrow. When you’ve had surgery for detached retina and a vitrectomy, the lens of the eye develops a cataract very quickly. My right eye is all foggy. When this surgery is over, it’ll be as clear and see as well as in its original state, before nearsightedness set in.

Eventually we’ll all be in our original state, if you want to go that far! Dust to dust. I’ll settle for the original I can imagine, being what’s called well, all systems working.

All systems working: I’m planning to go to the Writers’ Convention in Seattle in February. I’ve chosen to work with two MFA students this year in the Rainier Writing Program that I teach in. And I just launched my new book. No Need of Sympathy (BOA Editions). The party at Brilliant Books in Traverse City was spectacular. The owner, Peter Makin, always makes book launches an event. He’d gotten a cake (pictured), an exact replica of my book cover. Jim Crockett, retired from Northwest Michigan College, played guitar and sang. Jennifer Steinorth, who’s currently studying in the Warren Wilson MFA program, introduced me. I cried of course when I looked out at so many people who’ve supported me, brought me food, sent me cards and gifts, through my chemo and radiation. I feel surrounded by love, and simultaneously intensely aware of those who have to endure this godawful treatment with few friends and not-enough love.

All systems working: I’m planning to go to the Writers’ Convention in Seattle in February. I’ve chosen to work with two MFA students this year in the Rainier Writing Program that I teach in. And I just launched my new book. No Need of Sympathy (BOA Editions). The party at Brilliant Books in Traverse City was spectacular. The owner, Peter Makin, always makes book launches an event. He’d gotten a cake (pictured), an exact replica of my book cover. Jim Crockett, retired from Northwest Michigan College, played guitar and sang. Jennifer Steinorth, who’s currently studying in the Warren Wilson MFA program, introduced me. I cried of course when I looked out at so many people who’ve supported me, brought me food, sent me cards and gifts, through my chemo and radiation. I feel surrounded by love, and simultaneously intensely aware of those who have to endure this godawful treatment with few friends and not-enough love.

I’m pretty public. I was Delaware’s state poet laureate for seven years and am still in contact with many Delaware friends; I comment on poetry monthly for Interlochen Public Radio; I write a monthly poetry column for the Record-Eagle newspaper; I teach in the Rainier program; I give poetry readings. So when trouble comes, there are people aware of it. There are friends.

It was once otherwise. When my children were small, my marriage was falling apart, and I wasn’t yet teaching. my life was constricted, isolated. Lonely as hell. There’ve been other times, later, when I’ve been lonely as hell. I honestly do think, as Hilary Clinton wrote, it does take a village. It takes a village to raise children without trapping them within your own narrow prejudices; it takes a village to disperse some of the fear and anguish of a terrible diagnosis. To let some others help you carry it.

Most likely this is why I’ve loved writing this blog so much through all of this. You’re my village.