BOA Editions asked me to write a short interview with myself about No Need of Sympathy, to use as they considered book design and marketing. I invited myself to my study, where we talked over a cup of tea. We both are drinking green tea these days, for the antidioxants.

Fleda: Thank you so much for consenting to this interview. I'd like to begin with the title of your new book. You took your title from a Robert Creeley quotation, “Poetry stands in no need of sympathy, or even goodwill. One acts from bottom, the root is the purpose quite beyond any kindness.” Besides the obvious reference to poetry, I can’t help but note that you’ve just finished chemo and radiation for a serious cancer. Are the poems in this collection in some way a reflection of that?

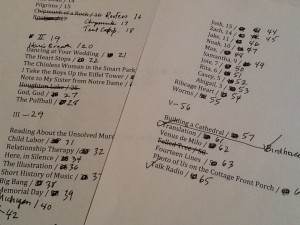

Self: As you may know, I’d finished this book before I knew I had cancer, but it’s interesting that “sympathy” works on the level of poetry and of personal distress. There are some poems that refer directly to poetry, but no, what I wanted, what I always want, is for the poems to reach “bottom” where the question of sympathy or lack of it is no longer an issue. To reach the place where we just SEE what is—cancer or anything else might come to mind—and that’s completely enough. There are poems about my father, my sister, my grandchildren, a chipmunk, Notre Dame, the Eiffel Tower, a giant puffball, child labor, Memorial Day. They’re all over the map, really. But I think they’re held together by the intent to see clearly, to get to the root.

Fleda: Science and modern physics seems to come into your poems frequently, even the ones that focus on family. And there is a Buddhist overtone. How do you reconcile those points of view?

Self: Buddhist thought and the most contemporary of scientific thought are really one and the same. Just like you and me. Western culture has taken a long time to see what was understood by others 2500 years ago—that there is nothing solid, that at the root, reality is in constant flux, and what we believe is “true” is our own projection. And of course this is what poetry has been doing forever—at least some of it—uprooting what we thought we knew, pointing us toward what can’t ever be exactly pinned down. So in poems like “The Purpose of Poetry,” “The Kayak and the Eiffel Tower”—my goodness, almost any one I turn to—I’m unseating what has seemed to be the case.

Fleda: Speaking of family, you have a sonnet sequence, each of ten grandchildren represented by one sonnet. Was this hard to write, to avoid sentimentality, or to figure what to say about each one so that they’d seem balanced?

Self: It WAS hard to write. I gradually eased them into their present sonnet form from a looser construction. They are as much about the grandmother, of course, since the grandchildren are seen through her eyes. The interesting part is that some are her natural grandchildren, some are step-grandchildren, and so she needs to acknowledge some difference, her own feelings of difference. I rewrote several of them over and over to get the right balance of honesty and care for the delicate feelings of those who have physical/emotional struggles. And her own struggles! The grandmother has her own background out of which all this has emerged. She’s learning and shifting all the while.

Fleda: We’ve followed your father, the death of your mother, your retarded brother, even your grandparents, through most of your previous collections. Do you find any shift in this one, any difference in your approach in your poems?

Self: So glad you've followed my poems! I think—who knows, but this is how it feels to me—that the poems that originate with family stories have gotten more deeply embedded in the culture, the world, the network of science and thought that support those stories. The stories are true, of course, but they suggest a lot more than their origin to me. My mind is seeing them as a kernel in the middle of a complex of things. There’s “Building a Cathedral,” that originated with the story of my father figuring how to get the cup to rotate in the microwave and stop with the handle pointed outward. That gets embedded in the building of cathedrals, his two “sweeties” and how he copes with that, his Windsor clock, “Waiting for Godot,” my grandmother’s rooster she made out of seeds in the last years of her life. And more. I am just ranging the territory that the original incident brings up.

Fleda: You have a number of poems that deal with social issues as well—Americans bursting down the doors of Pakistanis, inequality of wealth, poor young men being seduced into being soldiers, relationship therapy, child labor, and so on. Was it hard for you to combine these poems with the others and keep a cohesive collection?

Self: They seemed to me to naturally fall into place. After all, family issues are also political issues, and how things work scientifically is only a larger view of how they work close-up. I hope the collection is like a microscope that zooms in and out, sees the world writ large as well as the fine print, but it’s all one experience of being alive.

Fleda: Is there a consistent tone that you feel as you read through your own collection?

Self: The quotations that begin each section are meant to suggest that. Yes, I think of these poems as explorations into the nature of what’s real and what matters. There are no answers, but the questions are the crucial part. The line from Jane Hirshfield is what I mean: “Art, by its very existence, undoes the idea that there can be only one description of the real, some single and simple truth on whose surface we may thoughtlessly walk.” So, if I had to pick a “tone,” it would be curiosity, combined with deep love of being alive. Those may be one and the same. Another allusion to our own relationship, yes?