I thought you might like to read the text of a talk I gave last week at TEDx. I have to say, I was nervous. The TEDx event--a full day of speeches, each 18 minutes long--is meant to offer new ways to think and inspiration to act. The audience--in this case about 400 people in Traverse City--appears to be mostly business people and people in public service positions. The tickets are $100! It's amazing to me.My talk (which was accompanied by slides and soon will be out on YouTube on the TEDx site.) :I have been given the awesome task of concluding this TEDx. I figured I would take us out with a bang, with the most audacious topic I could think of: How Poetry and Meditation Can Save the World.I’d like to read you a poem. It’s one of my own. I wrote it from this painting (called “Swallow’s Game”) at an exhibit at the new Oliver Art Center in Frankfort:BirdhouseRemember the year we had bluebirds there?How they came back the next year, poked their nosesin and changed their minds? After that it was all swallows,after we knew to clean out the twigs to get the houseready for renters. Swallows or wrens. Oh, they mighthave been wrens, sometimes. They might have beenwrens all along, but I like the word swallow. I thinkthey were swallows. That tiny slender trilling downthe scale. Wrens sound like their bodies, compactand insistent. It was good to have either,and their chicks. Especially their chicks, evidentonly by the to-and-fro of the mothers, their fiercejudgments. It was good to have that life greet usat the corner of the house. Bluebirds, we felt blessed.They let us know who was in charge: blast, blast, chitter.Also the color, the royal robes. But the swallows,the way they swooped in and out! Who doesn’t lovethe word swooped? When they were crossingto the trees beyond our drive, remember how we’d sitin our kitchen chairs by the glass doors? It was sopeaceful to watch that industry, that tiny hopecarrying on, not caring a whit about us.Now I am going to make the absurd claim that a poem such as this one can save the world. And I am going to connect this to the practice of Buddhist-type meditation.First of all, I would like us to look closely at the poem, now that we’ve heard it. What does it do? It calls us, as the poet Richard Wilbur says in his own poem, “to the things of this world.” It pays close attention. It could have been about trash cans or sneezes or making love or anything else and do that, but in this instance, it’s birds.Well, it’s not about birds, is it? It’s about the speaker. It’s about her relationship with her husband, about a memory of a peaceful moment. Well, it’s not about that, either. It’s about stalling, staying in the moment of sounds.The word swooped. The sounds of birds. It holds us still. The line endings hold us, too. They encourage us to not rush on from point A to point B. We are asked to turn a corner before the end of a sentence, to make a brief pause before hurrying on. Each line is its own event. It’s set up to let each line be its own event.“And also the color, the royal robes. But the swallows”The thought isn’t finished, but its unfinished quality gives us a whole other way to think. We were on bluebirds, but then the line is overtaken by swallows. We know we’re about the turn the corner and find out what ABOUT swallows, but we’re momentarily held.It’s the holding that I want to talk about. We’re held with an image: royal robes. It becomes a kind of vision. It calls for completion.A king or queen in robes flickers in the corner of our eye. The bird and that flicker simultaneously collide in our minds. Unlike things. Our mind cannot completely unite them.Our minds also have to cope with the disruption of an unfinished line. We long to complete the meaning. For a moment, we’re held in mid-air. Is there going to be the meaning we expect, or another one?Jane Hirshfield, a poet I admire, says that “Art, by its very existence, undoes the idea that there can be only one description of the real, some single and simple truth on whose surface we may thoughtlessly walk.”You see where I’m going with this. A poem disrupts us. It will not allow us to move without thinking from point A to point B. It makes us stand in its small moments of silence and unknowing.The political ads, political TV shows are coming on thick and fast. Each one is absolutely confident of its truth, and of the untruth of the “other.” They are slickly crafted. They are not appealing to our ability to reason. They could care less about our reason, although they would like to seem that they do. They are instead slipping beneath the surface into our unconscious fears, our desires for security, for love, for community. They know where we live. We will not thwart them or turn them away by using reason.We will not save ourselves, apparently, by using reason, because the work of the ad is the work of a poem—to talk to us on a level we have no words for. In the space of silence and unreason.The difference between a political ad and a poem is that the ad is prying open the space of our fears and immediately capping it over with a so-called solution, a so-called perfect candidate who will save us. The poem opens us and leaves us open, gasping, awestruck at the space we didn’t realize was there. Some people are afraid of poems, and they should be. Osip Mandelstam, for one, died in a concentration camp in Siberia for writing poems that didn’t cap over the spaciousness of the mind with the party line.We stand in the middle of an art installation: “I don’t understand it,” we might say. But what if someone said that we would understand it if I we were told we were no longer awake, that what we see is a dream?It’s not only political poems and art installations that are dangerous.It’s the small, humble poems with birds, like mine, also. They train the mind to see its own spaciousness. They teach it not to grab for clichés. They teach it to trust uncertainty. To be willing to dwell there.So what does this have to do with morality and saving the world? You may be able to see where I’m going with this. I want to quote from a review of Brenda Hillman’s new book in the American Poetry Review. The review is by Melissa Kwasney. She begins by quoting a line from Hillman’s title poem: “It is nearly impossible to think about leading a moral life.”Kwasney goes on to say “It feels so especially now, particularly if one is an American. Given the enormity of our position (our responsibility for war, for recent tortures, for the Gulf filling with oil, the rapid extinction of species), the double meaning of the phrase—It is nearly impossible to think about—hits home.“We not only can’t think about it because the situation is cause for shame and despair; we can’t rely on only thinking as a way out of it. It won’t work. What will?In another poem, Brenda Hillman writes: “An ethics occurs at the edge/ of what we know.” But then she writes, “The creek goes underground about here.” We cannot see directly the subterranean force that connects us all, that we all depend upon. That makes us uncomfortable, sensing what we can’t see. We would rather slap that cap over it.How to live the moral life? Brenda Hillman’s poem says, “You should make yourself uncomfortable/ If not you who.”If we’re uncomfortable, we’re seeing directly that our comfort is built upon other people’s discomfort. So if we’re not made uncomfortable, who will be? Who will see what’s happening to the water, the earthworm, the fly, if we don’t?“I’m sick of irony,” Hillman says in another poem. “Everything feels everything.”It is the ability to feel that is the issue. To be able to counter the slick, polished surfaces of unfeeling, of our egos, it is necessary to re-learn to feel. Feeling is not done with the rational mind. The mind only slaps labels on our feeling, calls it “sorrow,” or “joy” or “anger” to feel it has control of them. Then the mind begins playing around with those words, finding causes and results, rationalizations, and so on. Feeling has no words and no excuses and no explanations. It simply is what it is.Here is a poem from the great and recently deceased poet Lucille Clifton’s Kent State poems, her response to the shooting of the students who were protesting the Vietnam war at Kent State University:surely I am able to write poemscelebrating grass and how the bluein the sky can flow green or redand the waters lean against theChesapeake shore like a familiarpoems about nature and landscapesurely but whenever I begin“the trees wave their knotted branchesand . . . .” whyis there under that poem alwaysan other poem?There is always another voice under our voice, calling. Perhaps that is why poetry seems intrinsically and eminently capable of doing this work of making the boundaries of the self unstable, whether the voice that answers speaks of its own life or that of others who are connected to it, in this case, the dead.What is the poet’s responsibility toward the political? We have a mission. The mission is not witnessing to the atrocities in the world. Poetry must witness to the invisible, not the visible.The poet Li-Young Lee says, “The poet shows how the invisible is more real than the visible—that the visible is merely a late outcome of an invisible reality that rules us the way the subconscious rules us. Our dreamscape is larger and rules us more than this waking state. We’re losing our bodies second by second. We can’t hold onto anything. It’s romantic to think we can. It is not our business to witness to any of this. No! The poet’s business is to witness the spirit, the invisible, the law.”A poem ultimately imparts silence. As it does that, as we feel that, we begin to be disillusioned. We are disillusioned of our ego’s small presence in order to reveal the presence of this deeper silence—this pregnant, primal, ancient, contemporary, and immanent silence.Meditation is about silence. And not. There is a misconception that the point of meditation is to get ourselves silent. Just try! It is impossible to “get ourselves” anything like that. The mind goes berserk when we sit quietly and do nothing else. We watch our minds be berserk. One sits and opens all the senses: sight, smell, touch, hearing. And thoughts—the mind is a sense, too. One pays attention. If the mind wanders into daydream, one notices when it returns.What happens in this kind of open meditation is that we begin to actually experience our lives, instead of experiencing what our stories tell us our lives are or should be. We begin to see our stories about ourselves as just stories about ourselves. As we pay attention, as we let things just go on without adding to them or subtracting from them, the mind tends to quiet down on its own. We begin to experience the space between words, between our ideas about things. We approach the often quite frightening space where we do not know anything, we don’t know what’s next, we don’t know what “meaning” is here, we don’t know what we should feel or think. But we feel and think anyway. This is our creative wellspring, the space some call God and some call peace. We are open. We are living beings. We see the content of our minds, but we don’t grasp at it as a fixed entity. When we begin to see this way, we are able to act with clarity and directness and genuineness based on what we actually see and feel, not based on our preconceptions or fixed ideas. We relate to people and nations as they are, not as what we imagine them to be.You can see how poetry and meditation are really the same. They require a willingness to hold still. They notice the silence. They notice what’s happening in and out of the silence. They are scary as hell. They bring us to the precipice of our prejudices. They ask us to dwell in what we don’t know. To allow the self-protective boundaries of the ego that we’ve built up over the years to soften and dissolve so that the real self, which is much larger and, as the poet Walt Whitman said, “contains multitudes,” can begin to function.Here’s a poem by Jane Hirshfield: Against CertaintyThere is something out in the dark that wants to correct us.Each time I think “this,” it answers “that.”Answers hard, in the heart-grammar’s strictness.Then if I say “that,” it too is taken away.Between certainty and the real, an ancient enmity.When the cat waits in the path-hedge,no cell of her body is not waiting.This is how she is able so completely to disappear.I would like to enter the silence portion as she does.To live amid the great vanishing as a cat must live,one shadow fully at ease inside another. Do we want to be a cat?No, but we want to live entirely within our lives, to know and not know, like the cat, acting out of what’s real and true and right in front of us. I lied. There is no “saving” ourselves or the world. We are all being spent by the minute. The greatest act of generosity is to let go of the last minute so that this one can be here, so we can see what best needs to be done, where our compassion must naturally flow, now. Our hope is in giving up hope in our gadgets and our noise and our absolute certainties and see what really is the case, at the moment, right now.

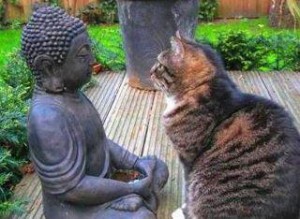

When we begin to see this way, we are able to act with clarity and directness and genuineness based on what we actually see and feel, not based on our preconceptions or fixed ideas. We relate to people and nations as they are, not as what we imagine them to be.You can see how poetry and meditation are really the same. They require a willingness to hold still. They notice the silence. They notice what’s happening in and out of the silence. They are scary as hell. They bring us to the precipice of our prejudices. They ask us to dwell in what we don’t know. To allow the self-protective boundaries of the ego that we’ve built up over the years to soften and dissolve so that the real self, which is much larger and, as the poet Walt Whitman said, “contains multitudes,” can begin to function.Here’s a poem by Jane Hirshfield: Against CertaintyThere is something out in the dark that wants to correct us.Each time I think “this,” it answers “that.”Answers hard, in the heart-grammar’s strictness.Then if I say “that,” it too is taken away.Between certainty and the real, an ancient enmity.When the cat waits in the path-hedge,no cell of her body is not waiting.This is how she is able so completely to disappear.I would like to enter the silence portion as she does.To live amid the great vanishing as a cat must live,one shadow fully at ease inside another. Do we want to be a cat?No, but we want to live entirely within our lives, to know and not know, like the cat, acting out of what’s real and true and right in front of us. I lied. There is no “saving” ourselves or the world. We are all being spent by the minute. The greatest act of generosity is to let go of the last minute so that this one can be here, so we can see what best needs to be done, where our compassion must naturally flow, now. Our hope is in giving up hope in our gadgets and our noise and our absolute certainties and see what really is the case, at the moment, right now.

How Poetry & Meditation Can Save the World

in Archive