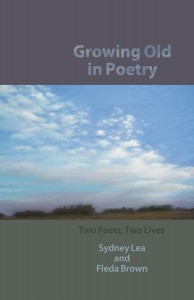

I’m leaning my bike against a tree for now, since I won’t see the doctor until tomorrow. I’ll report next week on what we learn, how chemo will go, and so on. In the meantime—you’ll see this is relevant—I want to tell you about a book I’ve co-written with Sydney Lea, called Growing Old in Poetry: Two Poets, Two Lives. It’ll be out from Autumn House Press in April exclusively (O brave new world!) as an e-book. I have had the BEST time writing this book over the last couple of years with my dear friend Syd.Syd and I share being poet laureate of our respective states. I’m former poet laureate of Delaware; Syd is the current poet laureate of Vermont. You should know his work, if you don’t. His eleventh poetry collection, I Was Thinking of Beauty, will be out soon from Four Way Books. The University of Michigan Press recently issued A Hundred Himalayas, a sampling from his critical work over four decades. A North Country Life: Tales of Woodsmen, Waters and Wildlife (Skyhorse Publishing), a third volume of outdoor essays, will be published in early this year.We had an idea that a book of essays from two people who’ve given their lives to poetry would be good reading. We then had the idea that if we picked topics and each headed out as we wished with that topic, we could cover a lot of territory, both artistic and memoirish. We picked our topics as we went along: some, such as “Wild Animals” are downright silly; some are, shall I say interesting, such as “Sex, “Music,” and “Food”; some are mundane but ultimately pretty revealing, such as “Clothes,” “Sports,” and “Houses.” The last one is called “Becoming a Poet,” but really, the whole collection is about us as people-poets. Poet-people. Poetry never completely goes off-stage.Here’s the beginning of one of my essays that’s less directly concerned with writing than some of the others. How ironic it is to me, now. I wrote this no more than six months ago. Our topic was illness. It begins this way:

I’m leaning my bike against a tree for now, since I won’t see the doctor until tomorrow. I’ll report next week on what we learn, how chemo will go, and so on. In the meantime—you’ll see this is relevant—I want to tell you about a book I’ve co-written with Sydney Lea, called Growing Old in Poetry: Two Poets, Two Lives. It’ll be out from Autumn House Press in April exclusively (O brave new world!) as an e-book. I have had the BEST time writing this book over the last couple of years with my dear friend Syd.Syd and I share being poet laureate of our respective states. I’m former poet laureate of Delaware; Syd is the current poet laureate of Vermont. You should know his work, if you don’t. His eleventh poetry collection, I Was Thinking of Beauty, will be out soon from Four Way Books. The University of Michigan Press recently issued A Hundred Himalayas, a sampling from his critical work over four decades. A North Country Life: Tales of Woodsmen, Waters and Wildlife (Skyhorse Publishing), a third volume of outdoor essays, will be published in early this year.We had an idea that a book of essays from two people who’ve given their lives to poetry would be good reading. We then had the idea that if we picked topics and each headed out as we wished with that topic, we could cover a lot of territory, both artistic and memoirish. We picked our topics as we went along: some, such as “Wild Animals” are downright silly; some are, shall I say interesting, such as “Sex, “Music,” and “Food”; some are mundane but ultimately pretty revealing, such as “Clothes,” “Sports,” and “Houses.” The last one is called “Becoming a Poet,” but really, the whole collection is about us as people-poets. Poet-people. Poetry never completely goes off-stage.Here’s the beginning of one of my essays that’s less directly concerned with writing than some of the others. How ironic it is to me, now. I wrote this no more than six months ago. Our topic was illness. It begins this way:

I loved being sick. If my body couldn’t work up the germs, my mind could. Through grade school, all the way through high school, I was deft at turning a slightly scratchy throat into a wicked possible strep condition that would keep me home from school. To cinch the matter, I would vigorously rub the thermometer, or hold it under warm water at the bathroom sink when no one was looking, I don’t know if my mother bought any of this, or if she was just too harried and/or depressed to fight me on it. The half-year my aunt Cleone and her three wildly healthy boys lived with us in Columbia, I would be “sick” and my Aunt Cleone would position herself at my bedroom door, frowning. “Fleda, are you really sick enough to stay home?” she’d ask. She was onto me, which almost spoiled my day, but not quite. Our house, in truth, was a house of illness. My brother was severely mentally retarded and had grand mal seizures so awful that each one would take your breath away. There was a heap of bottles, all full of potent drugs, on the kitchen counter, along with an apothecary’s mortar and pestle to grind up the ones too difficult for him to swallow. My mother had severe arthritis—no wonder. My father had only allergies, but he was able to make a great deal out of lying on his back on the bed with his head over the side, dripping Neo-Synephrine into a stuffed-up nose. Don’t get me wrong—we were also very physical. My mother loved to walk, arthritis or no. She could move really fast, her scarf tied under her chin like a Russian peasant; my father rode his bike several miles to school when almost no one did such a thing; my sister and I rode bikes, swam, played rudimentary tennis, and walked. But it appears to me now that the one way I could be assured that my parents’ attention would be directed at me was to be sick. And also, I was shy —I guess you could call it that. In any case, I found being at home, being taken care of, very comforting. My mother would have liked to be a nurse and seemed to enjoy having me home, bringing me poached egg on toast, straightening my covers, finding the paper-doll pages in McCall’s magazine for me, bringing me scissors and Scotch tape. The kid in Robert Louis Stevenson’s “The Land of Counterpane” was me: When I was sick and lay a-bed,I had two pillows at my head,And all my toys beside me lay,To keep me happy all the day. In fact, I remember lying there reading A Child’s Garden of Verses. They were too young for me, but I loved them anyway. School was always pressure—get the math problems right, do well on the test, and carefully manage to fit into certain groups of friends. I think I was a bit afraid of people. Being alone felt safer, easier. . . . in the mornings when my father was at school, teaching, and my mother was putting around, taking care of Mark and washing clothes, the house was quiet, peaceful—her little radio in the kitchen tuned to the Arthur Godfrey show or whatever followed that.

My essay has a postscript: “If I follow the lines of this essay, would I have to say that I brought this cancer on? Not on your life. I have a good life, and work that I’m eager to continue. I’m happy. I don’t want to stay home from school anymore.”Syd has posted his essay on “Music” on his website, http://sydneylea.blogspot.com/ . I think you’d enjoy reading it. I’ll post part of mine on music later. I must, however, get back to this illness thing. Such a nuisance.

My essay has a postscript: “If I follow the lines of this essay, would I have to say that I brought this cancer on? Not on your life. I have a good life, and work that I’m eager to continue. I’m happy. I don’t want to stay home from school anymore.”Syd has posted his essay on “Music” on his website, http://sydneylea.blogspot.com/ . I think you’d enjoy reading it. I’ll post part of mine on music later. I must, however, get back to this illness thing. Such a nuisance.