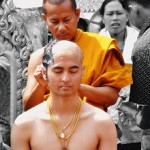

I think it might hang on one more day. I need a shower, so I put a nylon squeegee over the drain to catch hair. Oh, there’s quite a lot. When I get out, towel my head carefully, and run mousse through, large soggy heaps come out in my hands. I call Jerry. I take the scissors and cut the front as short as I can. Jerry cuts the back. No one is crying, no one is laughing. We’re doing a job here. My head emerges. The lines of my fontanels, visible for the first time since infancy. What is all this about hair? And teeth, I think, are the same. Aren’t we all drawn to life, blowing full in the breeze (Coleridge: “His flashing eyes, his floating hair!”) or chomping down on prey, asserting its aliveness. I look at myself in the mirror. Well, nice head shape, I think. And too, how strange to see what for most women, at least, is hidden all our lives.The shaved head! In the Middle Ages, denuding a woman of what was supposedly her most seductive feature was the typical punishment for adultery. In 1923, German women who were accused of having relations with the French were humiliated by having their heads shaved. And during WW II, the Nazis ordered German women accused of sleeping with non-Aryans to be publicly punished the same way.Prisoners often have their heads shaved, supposedly to stop the spread of lice, but also, of course, it’s demeaning.But Buddhist monks have their heads shaved, too—a sign of their commitment to the Holy Life, of one gone forth into the homeless life.

What is all this about hair? And teeth, I think, are the same. Aren’t we all drawn to life, blowing full in the breeze (Coleridge: “His flashing eyes, his floating hair!”) or chomping down on prey, asserting its aliveness. I look at myself in the mirror. Well, nice head shape, I think. And too, how strange to see what for most women, at least, is hidden all our lives.The shaved head! In the Middle Ages, denuding a woman of what was supposedly her most seductive feature was the typical punishment for adultery. In 1923, German women who were accused of having relations with the French were humiliated by having their heads shaved. And during WW II, the Nazis ordered German women accused of sleeping with non-Aryans to be publicly punished the same way.Prisoners often have their heads shaved, supposedly to stop the spread of lice, but also, of course, it’s demeaning.But Buddhist monks have their heads shaved, too—a sign of their commitment to the Holy Life, of one gone forth into the homeless life. I know a beautiful woman who has alopecia, and shaves her head. She’s as regal as Sinead O’Conner. I think also of many African American women who cut their hair as short as Obama’s, how lovely their heads often look, how much emphasis that puts on the neck, the eyes, the mouth. Beauty’s a matter of perception, highly influenced by genetic predisposition, I think.Yet, I’ve spent all these years looking at myself with hair. I have (had) nice hair. It has some body and although fine, is (was) still thick. I am surprised that I’m not more alarmed at having no hair, though. It is what it is. I have cancer. I don’t get to have hair and get rid of the cancer at the same time. Okay.Jerry and my hairdresser Jessica went with me to the wig place. Many women look beautiful with scarves and hats. I’ill wear hats sometimes in the house, but for me, looking in the mirror and seeing the same head I’ve always seen is a great morale booster. Also, I like it that when people look at me, I look the same. I’m not in denial. Everyone who knows me knows I have a serious cancer. And I’m writing this blog, for heaven’s sake! But wearing hair allows me to move among strangers without having them more internally focused on “Oh, that poor woman,” and more on what we’re talking about.I spent some time deciding who I should be. Perky? Vampy? Blonde? I settled on the person I’m used to. I sent my daughter a picture. She said she’d been trying to get me to get my hair cut like that. So when I have hair again, shall I tell Jessica to cut it like my wig?

I know a beautiful woman who has alopecia, and shaves her head. She’s as regal as Sinead O’Conner. I think also of many African American women who cut their hair as short as Obama’s, how lovely their heads often look, how much emphasis that puts on the neck, the eyes, the mouth. Beauty’s a matter of perception, highly influenced by genetic predisposition, I think.Yet, I’ve spent all these years looking at myself with hair. I have (had) nice hair. It has some body and although fine, is (was) still thick. I am surprised that I’m not more alarmed at having no hair, though. It is what it is. I have cancer. I don’t get to have hair and get rid of the cancer at the same time. Okay.Jerry and my hairdresser Jessica went with me to the wig place. Many women look beautiful with scarves and hats. I’ill wear hats sometimes in the house, but for me, looking in the mirror and seeing the same head I’ve always seen is a great morale booster. Also, I like it that when people look at me, I look the same. I’m not in denial. Everyone who knows me knows I have a serious cancer. And I’m writing this blog, for heaven’s sake! But wearing hair allows me to move among strangers without having them more internally focused on “Oh, that poor woman,” and more on what we’re talking about.I spent some time deciding who I should be. Perky? Vampy? Blonde? I settled on the person I’m used to. I sent my daughter a picture. She said she’d been trying to get me to get my hair cut like that. So when I have hair again, shall I tell Jessica to cut it like my wig? Here I am with the wig. Next, the eyebrows and lashes will go. They’re already thinner.

Here I am with the wig. Next, the eyebrows and lashes will go. They’re already thinner.

My Wobbly Bicycle, 9

in Archive