Well, this was a surprise. My chapbook, Doctor of the World, just won the Finishing Line Press’s Open Competition! If you, like my brother-in-law, are not one of the poetry cognoscenti, and have to look up the term chapbook: it’s really just a short collection, usually under 30 pages.

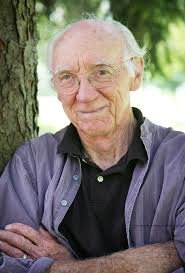

Harry Humes

Many years ago, my friend Harry Humes, in Kutztown, PA, published something chapbook-like for me as one of a series in his journal, Yarrow. I think I still have some copies somewhere. I just looked Harry up. He’s done so well since then, and well deserved. A sweet and generous man, 88 years old, a heck of a poet. He’s one of the people who boosted me on my way, who had confidence in me before I knew what I could do, myself.

Doctor of the World is all prose poems. Again, a term non-poets might find mysterious. We’ve come to think of a poem as a language-object that leaves space at the end of the lines. And/or having rhyme, or a regular rhythm. A prose poem looks like prose but reads like poetry. You can find prose poems in the Bible, in Wordsworth, but the form is usually traced to the nineteenth century French symbolist writers like Charles Baudelaire. Rilke, Kafka, Neruda, and Paz all wrote prose poems, and in this country, William Carlos Williams and Gertrude Stein, James Wright and Charles Simic.

This is an age of overwhelmingly speedy transitions. Of boundarylessness, of slippage of forms. This is an age of sex change, of wearing tennis shoes with a tux. Sometimes it’s hard to tell what a poem is. Frankly, who cares? The label is not the issue. The issue is, are the words intimate, original, do they cause you to hear language differently, do they take you out of the mundane, do they take the top of your head off.

I don’t know why I have written so many prose poems. It isn’t the influence of other writers particularly. It’s more how I felt when I wrote them. I felt I was spinning a moment in time, tracing my mind in a way that kept going almost obsessively, refusing to pause until it was done.

Obsessive is the right word. I’d say this is the true nature of a prose poem. There’s something that wants to keep moving, all the way to the margin. That pressure. There are prose poems, a number of them, in my last book, Flying Through a Hole in the Storm.

The boundary between the poem and the lyrical essay is also slippery. The prose poem feels like a wadded-up (clean!) Kleenex, one part touching another in a seemingly random way, but you can feel the sense of it, a moment in the mind. A lyrical essay spreads the Kleenex out on the table, still wrinkled. The wrinkles are where it wanted to stop in its tracks and admire itself as a poem. The spread out is where it wanted to keep moving.

A chapbook has some advantage over a full-length collection. It’s short enough to read in one sitting, so it can feel cohesive, one voice. Not that a larger collection doesn’t have that, but the chapbook’s tone may be easier /quicker to feel. Like flash fiction, like the short story. A larger collection can give you what a novel does—a fuller sense of the world of the poet/poem, a marriage rather than an affair, something like that.

Really, I’m just as pleased to have this small collection as I am with a larger book. Meanwhile, my full-length collection is out there in the hands of editors. I’m hoping, as poets do. It’s nearly always 50% hope, 30% confidence, and 20% despair, or some variation. Then there’s my prose “diary” of moving into a senior living place. More waiting. It is always thus, unless you’re one of the Chosen Few who have a press panting for your next book.

I’ll be writer-in-residence at the Interlochen Writers’ Retreat next week—always fun and energizing. I’ll tell you about that later.