I don’t know whether it’s the cottage itself, or its long history for me, or simply the fact that I’ve historically had more writing time, but it’s true that more poems, more writing has happened here for me than anywhere else.

I’m sad because there are so many fewer birds at the feeder. I’m sad because there’s only one lone bat that returns at night to our upper porch. I’m sad because of diminished fish, frogs, turtles, almost no crawdads. I’m sad because the hemlock disease is creeping our way, up from slightly south of here. We’ve already lost our beech trees.

It's hard to know how to live with so much loss. But live we do, and there’s a lot to be glad about. The waves slosh on the rocks as of yore. The sun mottles the leaves, Ollie is enraptured at the tiny creatures climbing the screen.

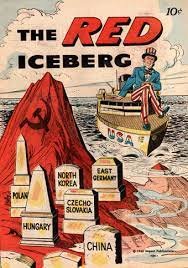

I suppose all times have been truly apocalyptic to the ones living them. Even the somnambulant 50’s had the Korean War, McCarthy, the Atomic bomb. They seemed as terrifying to us then as the destruction of the planet is now. The tiniest itch can drive you crazy, in other words. Magnitude matters only when you back off a few years, or centuries. Whatever you write, if you’re writing, is the center of the universe.

W.G. Sebald

I’m reading the great German writer, W. G. Sebald. I’d read The Rings of Saturn years ago, wasn’t ready for it, then read it again later. I’m reading his last book, Austerlitz. His books are utterly unique. They combine memoir, fiction, travelogue, history, and biography. You can’t read him quickly. There’s very little in the way of plot. You have so sink into his prose, move with it.

Susan Sontag, in a 2000 essay in the Times Literary Supplement, asked whether “literary greatness [was] still possible.” She concluded that “one of the few answers available to English-language readers is the work of W. G. Sebald.”

He’d published as an academic, but got frustrated by that. He began to write something that borders fiction, borders memoir. He called it “documentary fiction.” Who knows what it is? (It’s not Truman Capote-esque). It keeps a reader disoriented. No one else writes like him. I mention him here because of the blurring lately of the boundaries of fact, fiction, prose, poetry. We’re at this great upheaval, aren’t we, in all aspects of human existence. We have no stable ground to stand on. It seems necessary to go at things obliquely, to see what might come of that.

Genre, sexual identity, religion, nationality, race, all are blurring. What does it means to be a poem, a woman, a White woman, a Black man, an American, a Mexican? On and on. Will we sort it out and fall into categories again, but different ones? Maybe not in the same way. I can’t predict. I can say that categories have gotten us into a lot of trouble, defending the borders.

But at some point you do have to choose which bathroom you’ll use. At least in this country. And at some point, a poem is no longer a poem, right? These aren’t moral choices. They’re observational choices, you might say. Too complicated to go into here.

Mark O’Connell says in a 2011 New Yorker essay, “Reading [Sebald] feels like being spoken to in a dream. He does away with the normal proceedings of narrative fiction—plot, characterization, events leading to other events—so that what we get is the unmediated expression of a pure and seemingly disembodied voice. That voice is an extraordinary presence in contemporary literature, and it may be another decade before the magnitude—and the precise nature—of its utterances are fully realized.”

Representative 19th Century poet/critic. :)

This may be the way it is. We gradually adjust to shifts in the way we understand categories. Like poetry. I try to imagine what a nineteenth century poet/critic would have thought, turning the pages of, say, today’s Poetry Magazine. “Egads! he [it would be a he] would say. “You call this poetry?” But people have been saying that forever. That’s how new things come into being.