While the water’s glassy, about 6:30 a.m., the ducks come by with their brood, five or six of them. I can’t be sure, they pack themselves so close together and are so small. They drag the water into a shimmer behind them and move on up the lake. I’m glad I came out here on the dock before the breeze picks up. The ducks hang along the shoreline so they can dip and nibble at the grasses. All beings fit where they belong. Big fish deep under, minnows near the surface, water striders on the slight tension of the surface. As the sun starts through the trees, it draws lines along the grass. So much turmoil, riots, wars, crumblings, and there’s still grass. One doesn’t make up for the other, or provide an antidote to the other. There’s one, and the other: same basic materials, right? But shaped into mountains and valleys.

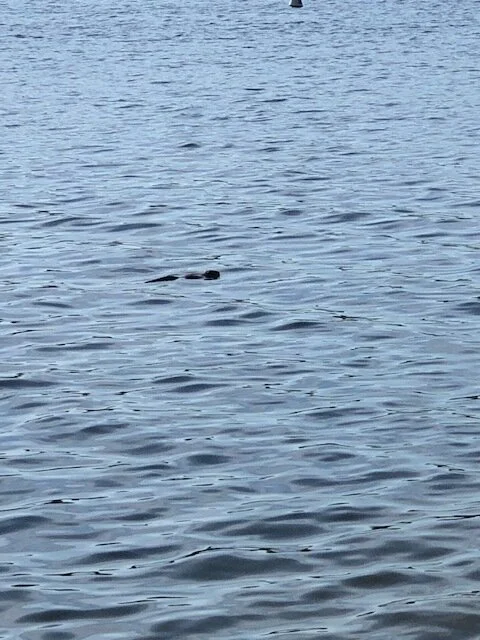

There’s also our resident beaver, or otter, or mink. Or muskrat, which is what my sister thinks. I’m inclined toward mink, but I can’t get a good enough look. I went out on the dock last night and saw it floating leisurely on its back. When I can’t see it, I can see its wake.

All this exquisite beauty, and also, the demonstrations, riots, murders, not to mention, my god, beheadings. Some people are more inclined toward despair, and I often think it’s warranted. It may be accurate. But the slough of despond feels sticky. You can get your boots stuck in it. I notice that environmental organizations figured out that despair doesn’t help. They’ve been publishing their successes, however small. Not that anyone wants to stand at the end of the dock with a beatific smile while Rome burns. (Sorry about mixed allusions). I suspect that beauty and horror have always gone hand in hand. It takes practice to hold them both in mind, but holding them both in mind is most accurate.

The Puritan theologian Jonathan Edwards’ famous 1741 sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” paints a ghastly picture of the hell that awaits sinners. You gotta force them to their knees, make them repent. It’s the old radical mind-split—evil over here, good over there. Your job was to get yourself out of one place, into the other. Which I guess can work for a while. You can force people to do stuff. You can force the police not to shoot at Black men just because they’re Black. For a while, maybe. It worked a little during our long self-congratulatory honeymoon with Obama, that temporarily hid the faces of the furious, the racist, from our view.

This photo has no relation to anything, but I think it’s gorgeous. I took it at 10:00 one night this week.

I’m pretty sure that a dam (or wall) can’t be built high enough or strong enough to separate good and evil. Or black and white. We just took down the dams along the Boardman River here in Traverse City. The river is slowly spreading itself out, finding its new limits. The limits are there and are natural, following the contours of the land. I can’t take this image and make it fit exactly what I’m thinking, but it’s something to do with seeing the self-constructedness—of what we once thought would make good barriers, of quitting our belief in them, so that people can breathe.

I mean the barriers set up by judgments, and even of our own (perfectly justified) guilt. All guilt does is make another barrier. “I” did this to “you.” When you think about it, it’s far, far, more complicated than that. I’m thinking that what needs to be done will begin to show itself more or less naturally as the artificiality, the sheer arbitrariness, of the so-called barriers begins to be obvious.

Update: I had my first swim of the season today. I was swimming not 20 feet from the first loon I’ve seen this season. Pure heaven, you might say. Also a leech attached itself to my hand. By the time I saw it, my hand was a bloody mess. Pure Hell. You might say.