A friend made us masks. When I wore mine, it was forever sliding up in my eyes, and I was forever pulling it down, which totally violates the no-touching-your-face rule. So I sewed down a small fold in the top of it and ran a couple of plastic twistees through. That wasn’t stiff enough, so I added a large straightened paper-clip. Voila! I can bend it to shape my nose and it doesn’t ride up. I also made tucks in the elastic so it fits tighter.

It is a pleasure to be inventive. It is a pleasure to figure out what you can cook with what’s already here. Maybe it’s just me, but it’s a pleasure to have to make do. We weren’t really poor when I was a child, I guess, but it seemed that way. We were six, including my brain-damaged brother who needed expensive medicine, all living on an assistant professor’s salary. (My father had no inclination to finish his dissertation and thus get promoted). My parents were forever having to ask their parents for money. If you wanted something, you’d better figure how you can conjure it up from what you have.

This could turn into one of those tales about the good old days when people had to struggle through on their own. Okay, it’s one of those tales. There is something deeply satisfying to me to get out my needle and thread and figure out how to sew a seam that will fix a problem.

After my father’s leg was amputated, I cut off the right leg of several pair of pants and stitched the hems by hand (because I had stupidly sold my sewing machine when we moved to our condo.) I got as much pleasure out of that little job as I get out of working on a poem. It’s all figuring out what to do.

Life was, ahem, unsteady for me as a child. It wasn’t so much rolling with the (metaphorical) punches as it was figuring out what to do next that made me feel, if not happy, at least satisfied, clever, able.

The edges of our driveway were overrun with irises. The yard was overrun, period. I was maybe, what, 13? out there by myself with a trowel, digging like crazy to make some order. Metaphor, sure, but it does work, to show some personal agency when things are out of your control.

I head for the grocery in my hazmat suit: coat, gloves, hat, mask. Jerry has arranged the list for me in order of where things can be found, so I can make a fast trip of it. When I return, we wipe down every item, plus the bags, with a mixture of bleach and water I put in a little sprayer bottle. I get in the shower; Jerry puts my clothes in the washer. I quarantine my coat and wool hat for several days and wear a different one.

“Contemplate the preciousness of human life, being free and well favored. This is difficult to gain and easy to lose. Now I must do something meaningful.”

Don’t think for a minute I’m not choking with tears for the ones who are sick, who are dying. But there is this small pleasure in life: figuring out how to live here and now. I have this one confined living space, containing my life. What will I do with that? How will I cleverly use it? Will I write poems? Will I write prose? What will we watch in the evenings? Will we try having pizza delivered here on the third floor, with the doors locked below? How will that work? Okay, we will!

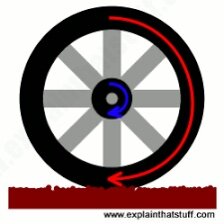

Surely you know what I mean. It’s the solid earth, it’s gut-level, old fashioned need to survive that sharpens your vision, clarifies your actual needs. And when you’re sad and/or numb with grief, add that in, too. Touching solid earth. You know how a wheel works? It digs in to rotate. It’s a force-multiplier. It uses the hard earth to provide leverage.