Sunday was glorious. Jerry and I drove to Empire and walked on the Lake Michigan beach, looking over at Sleeping Bear Dunes, and then we drove to Glen Arbor a few miles away and walked that beach, then ate lunch at an outside table. Lake Michigan is about as head-clearing as they come—blue, clear, seemingly limitless as the ocean.

Sunday was glorious. Jerry and I drove to Empire and walked on the Lake Michigan beach, looking over at Sleeping Bear Dunes, and then we drove to Glen Arbor a few miles away and walked that beach, then ate lunch at an outside table. Lake Michigan is about as head-clearing as they come—blue, clear, seemingly limitless as the ocean.

Nothing but transitions: Tuesday—yesterday—was my second-to-last chemo, a week late. My platelet score was still one point too low, but the decision was to go ahead, but lower the dose of carboplatin a bit. There’s no guarantee that I’ll be able to have the next chemo in 3 weeks. It might be 4 again. But we can hope. It’s better to have them as close together as possible.

Another struggle with the IV. My thin, slippery, and tired veins eluded the first three efforts. The expert was called in again and after a lot of careful tracing up and down my arm, tapping and thinking, she inserted the needle once into the right place. But it was a tender vein and I needed a warm pack on it. Total drip time is about 4 ½ hours. Photo shows my sad arm.

So, I asked my oncologist. What happens when I’m finished? What do you look for and how often do you check? He said I’ll have a scan at 6 months, another at a year, and one a year after that. “But frankly, he says, “it doesn’t matter. We hit you hard with this treatment because, considering your level of cancer, if it comes back, it will take your life.”

Oh.

We talk about statistics while my mind is still reeling. “I told you not to pay any attention to statistics,” he says. “You’re not a statistic.”

Okay, here’s what I haven’t said before: the 5-year (typical marker) survival rate for this cancer is 35-65% (I’ve also been told by the radiation oncologist that it’s probably as high as 85% these days). But the numbers aren’t clustered around 50%. There’s a huge standard deviation, so these rates are made up of survivors widely scattered along the continuum, many of those people obese, with diabetes and other health problems.

Back to the oncologist: “You’re thin, you have good health habits. I told you before you shouldn’t have this cancer. I have good expectations (Did he use those exact words? I wish I could remember) for you to be in that upper group.”

I’m always scared when he walks into the room. Time to face the music. He’s blunt. He gives me the unvarnished truth, and then backs up and tries to varnish it a little. But this is the way he is—a surgeon and researcher. But I’m also grateful. There’s a peculiar relaxation in knowing that this is it. There’s no ambiguity. If it comes back, there may be ways to retard its growth for a while, but that’s all.

I don’t think it will come back. That’s the truth. That’s what my mind and body tell me.

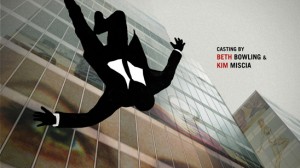

But: Transition again: Mad Men’s opening sequence has a silhouette of a man falling, with a tall corporate building in the background. He doesn’t begin from anywhere; he doesn’t end anywhere. He’s just falling. Entirely unmoored. This, it seems to me, is what life is when we see it clearly. Nothing to hang onto. Everything changing constantly.

But: Transition again: Mad Men’s opening sequence has a silhouette of a man falling, with a tall corporate building in the background. He doesn’t begin from anywhere; he doesn’t end anywhere. He’s just falling. Entirely unmoored. This, it seems to me, is what life is when we see it clearly. Nothing to hang onto. Everything changing constantly.

We love what we love. We want it—and ourselves—to last. But what is it we want to last? A collection of thoughts about who we are. Even they change. But beyond the changing—and this is where my years on a cushion pay off—is a vastness made up of that changing but itself deeply comforting when we’re able to see through (not reject) the changing. Why even try to talk about this? Words play out. But it seems useful to at least let the words point toward it. Poetry is best at this. When a poem causes us to suck in our breath and have nothing to say, it’s pointing. When there’s no way to say what it’s pointing toward, it’s pointing.