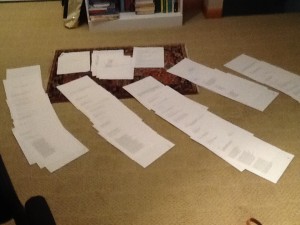

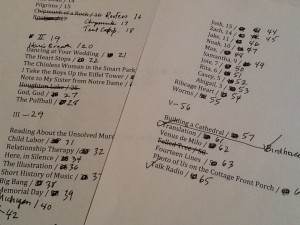

A collection of poems, stories, or essays has to be arranged, of course. There’s always the default: chronological, either by content or by date written. There’s something to that, since that gives a history of your mind on its travels. But perchance--likely, in fact--there’s a different kind of history—more of a dance—only discernible when the whole is in front of you. I don’t know any other way to do this arranging, myself, but to print out the whole manuscript and lay pages out on the floor—I’m talking about poems, now. With essays, it’s easier to keep the larger blocks in mind.I had my new book, No Need of Sympathy, ready, naturally, a year or so ago when I signed the contract with BOA. It was the best book I could put together at the time. But the book won’t come out until next October, so, anticipating that they’ll ask me for a final version just after the first of the year, I went back to work on it last week. I’ve revised a little bit. And I have a few new poems I think will work better, and a few that I’m glad to have the chance to pull out. And I’m asking myself if I still agree with myself about what goes in each section.At nearly the same time, I’m reading my friend Sydney Lea’s new collection he’s putting together. Both his and mine are made up of individual poems, written at separate times without reference to anything ongoing, other than being part of the world we live in and reflective of the coherence of our own minds. The course of his book seems to be an emotional movement—elegaic, dark, then lyric.So many books of poems—as well as short stories—by young writers have a deliberate and prominent narrative arc. The better, I think, to rope in people who need to be pulled along to get them to read the book, which may be the state of things.One With Others, C.D. Wright.’s new book. (Well, she’s not young.) Are they poems? Are they prose? Not at all sure. There’s clearly a narrative, sustained characters, the evolution of the civil rights movement. Yet the long lines, sentences, have the feel of an epic poem.I digress. But not really. Shall I depend on the reader to be content with poem after poem, each with its own private narrative arc? (Even the lyric has a narrative undercurrent.) Or, shall I aim for a book-sized narrative, like Wright’s, or at least set the book up so that one poem hints what a later one completes?Other issues: I tend to like books with sections. I like to be stopped by a section-marker, asked to consider what these poems have in common. I like (sparely used and unpretentious) epigraphs as an added dimension, another way to relate to the poems. In other words, I like all the help I can get. All the dynamics of this writer’s world I can get.

I don’t know any other way to do this arranging, myself, but to print out the whole manuscript and lay pages out on the floor—I’m talking about poems, now. With essays, it’s easier to keep the larger blocks in mind.I had my new book, No Need of Sympathy, ready, naturally, a year or so ago when I signed the contract with BOA. It was the best book I could put together at the time. But the book won’t come out until next October, so, anticipating that they’ll ask me for a final version just after the first of the year, I went back to work on it last week. I’ve revised a little bit. And I have a few new poems I think will work better, and a few that I’m glad to have the chance to pull out. And I’m asking myself if I still agree with myself about what goes in each section.At nearly the same time, I’m reading my friend Sydney Lea’s new collection he’s putting together. Both his and mine are made up of individual poems, written at separate times without reference to anything ongoing, other than being part of the world we live in and reflective of the coherence of our own minds. The course of his book seems to be an emotional movement—elegaic, dark, then lyric.So many books of poems—as well as short stories—by young writers have a deliberate and prominent narrative arc. The better, I think, to rope in people who need to be pulled along to get them to read the book, which may be the state of things.One With Others, C.D. Wright.’s new book. (Well, she’s not young.) Are they poems? Are they prose? Not at all sure. There’s clearly a narrative, sustained characters, the evolution of the civil rights movement. Yet the long lines, sentences, have the feel of an epic poem.I digress. But not really. Shall I depend on the reader to be content with poem after poem, each with its own private narrative arc? (Even the lyric has a narrative undercurrent.) Or, shall I aim for a book-sized narrative, like Wright’s, or at least set the book up so that one poem hints what a later one completes?Other issues: I tend to like books with sections. I like to be stopped by a section-marker, asked to consider what these poems have in common. I like (sparely used and unpretentious) epigraphs as an added dimension, another way to relate to the poems. In other words, I like all the help I can get. All the dynamics of this writer’s world I can get. Some thoughts:1. I had a group of flower poems in Reunion. I had placed them together. My friend Dabney Stuart said to separate them, to spread their energy throughout instead of lumping it up. He was right and that’s a useful way to think about “groups” of poems. But I have a series of 10 “Grandmother Sonnets” in this new book. It makes no sense to separate them. They depend upon each other in some way. There’s kind of a movement.2. Sometimes I don’t know what a section is for, or why it’s there, but it feels right. The poems in any section could go in some other, by just thinking of them a bit differently. But generally the reader is willing to play along with the way the writer’s thinking.3. Almost any way the poems/stories/essays get arranged will have some sense to it. The writer’s mind is the container, and so everything fits, in some quirky or mundane sense.4. Arranging poems/essays/stories is really writing another poem/essay/story (Frost said this, not me). The whole needs to feel like a whole. Not anything like the sharp click of a box lid. More like a sense of having been visited by an alien being: there’s an entrance, an amazement, an exploration, and then a leaving, with the wafting of that other world still hanging in the air, doing its work.

Some thoughts:1. I had a group of flower poems in Reunion. I had placed them together. My friend Dabney Stuart said to separate them, to spread their energy throughout instead of lumping it up. He was right and that’s a useful way to think about “groups” of poems. But I have a series of 10 “Grandmother Sonnets” in this new book. It makes no sense to separate them. They depend upon each other in some way. There’s kind of a movement.2. Sometimes I don’t know what a section is for, or why it’s there, but it feels right. The poems in any section could go in some other, by just thinking of them a bit differently. But generally the reader is willing to play along with the way the writer’s thinking.3. Almost any way the poems/stories/essays get arranged will have some sense to it. The writer’s mind is the container, and so everything fits, in some quirky or mundane sense.4. Arranging poems/essays/stories is really writing another poem/essay/story (Frost said this, not me). The whole needs to feel like a whole. Not anything like the sharp click of a box lid. More like a sense of having been visited by an alien being: there’s an entrance, an amazement, an exploration, and then a leaving, with the wafting of that other world still hanging in the air, doing its work.

Putting Together a Book

in Archive