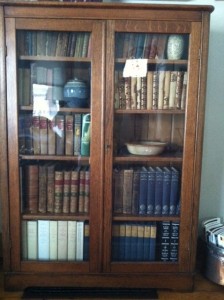

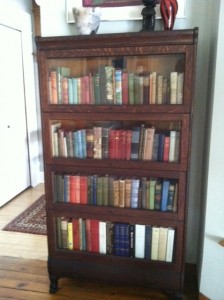

We have six bookcases downstairs. The two glass-fronted ones in the living room hold the old books, the ones with tarnished gilt on the covers. Some covers are leather, some are falling off. There are four different early editions of the works of Tobias Smollet, the writer my husband spent a good part of his career writing about and editing his works. The works of Thackeray, Fielding, Maria Edgeworth. The pages are stiff, delicate, spotted. These books reside in our house in the category of memory. We don’t read them: they stand for literature. They honor the past. The other one in the living room was my grandparents’ and holds many of their books, including some written by my economist grandfather. The others range from Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class. Tales from Shakespeare, an old Gulliver’s Travels, collected poems of Paul Lawrence Dunbar, to The Three

We have six bookcases downstairs. The two glass-fronted ones in the living room hold the old books, the ones with tarnished gilt on the covers. Some covers are leather, some are falling off. There are four different early editions of the works of Tobias Smollet, the writer my husband spent a good part of his career writing about and editing his works. The works of Thackeray, Fielding, Maria Edgeworth. The pages are stiff, delicate, spotted. These books reside in our house in the category of memory. We don’t read them: they stand for literature. They honor the past. The other one in the living room was my grandparents’ and holds many of their books, including some written by my economist grandfather. The others range from Thorstein Veblen’s Theory of the Leisure Class. Tales from Shakespeare, an old Gulliver’s Travels, collected poems of Paul Lawrence Dunbar, to The Three  Little Cottontails. One downstairs bookcase holds random 20th century novels we haven’t been able to part with for no good reason. One big bookcase in Jerry’s study is arranged according to the history of literature, from Aeschelus to Norman Mailer. This arrangement is for my benefit, so I can look upon history and more or less keep it straight. The other two there are his, arranged in some inexplicable way that suits him.My study upstairs was an attic and has a strongly pitched ceiling. So I have five low bookcases. Five years ago, when we moved here, I arranged my poetry books for the first time. Poetry books are thin, easily lost, easily slipped back between two others. So I decided to alphabetize them all, by author, so I’d know what was there. This was a long process and involved spreading them out on the floor like decks of playing cards. I decided to split them into poetry-by-women and poetry-by-men, for ease of location. This has been a good plan. I am aware how many more are by men than by women. This is a subject of a blog all its own.I have a group of anthologies, a group of collections of essays on poetry by poets. . . . . oh, I’ll bore you if I keep on. One last thing: I have a bookcase with one shelf of Christian reference books, including the little white Bible given me when I was baptized, and a larger, now, row of Buddhist reference books. These represent the evolution of my vision of how things are, in general.Arranging is good for the soul, at least good for mine. It helps me find things, which is a way of being aware of each object. It helps me see where I fit into the scheme that humans have devised. I know that books turn to dust, that the ones I write will turn to dust. Some have no doubt already been shredded or incinerated or are molding in landfills. No matter. Kindles and IPads are great, efficient tools. But what I plan to keep around me as long as I live are reminders of great thought, of those who aspired to greatness, of those who looked for Truth in all good faith and honesty.T. S. Eliot would have called them objective correlatives. They stand for the convolutions and amazements of the human mind in action. They stand for the imaginary worlds we invent that sometimes actually point to the truth of things. At the end of Four Quartets, Eliot wrote:We shall never cease from explorationAnd the end of all our exploringWill be to arrive where we startedAnd know the place for the first time.

Little Cottontails. One downstairs bookcase holds random 20th century novels we haven’t been able to part with for no good reason. One big bookcase in Jerry’s study is arranged according to the history of literature, from Aeschelus to Norman Mailer. This arrangement is for my benefit, so I can look upon history and more or less keep it straight. The other two there are his, arranged in some inexplicable way that suits him.My study upstairs was an attic and has a strongly pitched ceiling. So I have five low bookcases. Five years ago, when we moved here, I arranged my poetry books for the first time. Poetry books are thin, easily lost, easily slipped back between two others. So I decided to alphabetize them all, by author, so I’d know what was there. This was a long process and involved spreading them out on the floor like decks of playing cards. I decided to split them into poetry-by-women and poetry-by-men, for ease of location. This has been a good plan. I am aware how many more are by men than by women. This is a subject of a blog all its own.I have a group of anthologies, a group of collections of essays on poetry by poets. . . . . oh, I’ll bore you if I keep on. One last thing: I have a bookcase with one shelf of Christian reference books, including the little white Bible given me when I was baptized, and a larger, now, row of Buddhist reference books. These represent the evolution of my vision of how things are, in general.Arranging is good for the soul, at least good for mine. It helps me find things, which is a way of being aware of each object. It helps me see where I fit into the scheme that humans have devised. I know that books turn to dust, that the ones I write will turn to dust. Some have no doubt already been shredded or incinerated or are molding in landfills. No matter. Kindles and IPads are great, efficient tools. But what I plan to keep around me as long as I live are reminders of great thought, of those who aspired to greatness, of those who looked for Truth in all good faith and honesty.T. S. Eliot would have called them objective correlatives. They stand for the convolutions and amazements of the human mind in action. They stand for the imaginary worlds we invent that sometimes actually point to the truth of things. At the end of Four Quartets, Eliot wrote:We shall never cease from explorationAnd the end of all our exploringWill be to arrive where we startedAnd know the place for the first time.

Arranging The Books

in Archive